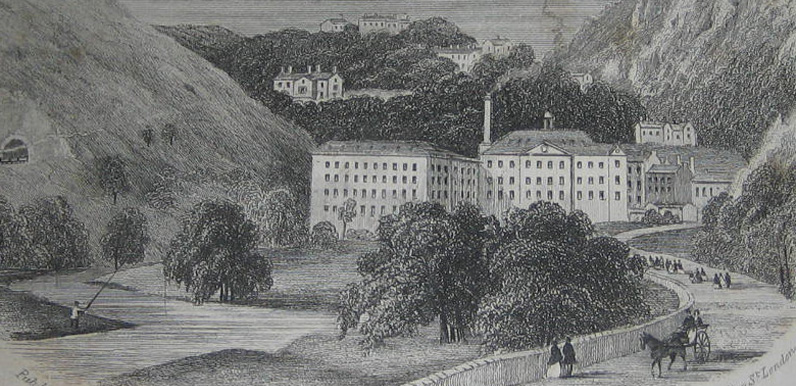

Above: An 18th century etching of Cressbrook Mill with Cressbrook Hall and Cressbrook village on the hills behind. (Image courtesy of Alan Roberts.)

Cressbrook lies beside the Rive Wye about half a mile east of Litton. John Baker was first to develop the site – to grow and distill peppermint, lavender and other aromatic herbs which he grew on land beside the river with the wonderful name of Water-cum-Jolly.

Sometime around 1779 he leased the land to Richard Arkwright, who became known as the father of the industrial revolution for his innovative use of water power to mechanise cotton production, earning himself a fortune in the process

Above: Click the ‘Now’ button, or drag the green slider, to compare Cressbrook Mill in the early 1900s with today’s satellite view. Litton Tunnel at bottom left is on the Monsal Trail.

The first mill on the site was built around 1783 by William Newton, who also had a stake in nearby Litton Mill. Cressbrook Mill was destroyed by fire just two years later in 1785. The mill was uninsured and Newton was dismissed by Arkwright who had a notoriously fierce temper.

Arkwright died in 1792, leaving the mill to his son, also called Richard, who then sold it to his cousin, Samuel Simpson. The mill went bankrupt in 1808, and lay closed until 1810, when it was purchased by two Manchester cotton spinners, John and Francis Philips.

The brothers soon added a second mill, which is the large four-storey building that dominates the site today. They also persuaded Newton to return. Known as the ‘Minstrel of the Peak’ for his poetic skills, Newton seems to have earned a more sympathetic reputation for the treatment of his child labourers, compared to the owners of Litton Mill.

Above: Sir Richard Arkwright earned fame and fortune for his innovative cotton spinning machines, creating the world’s first water-powered mill at Cromford.

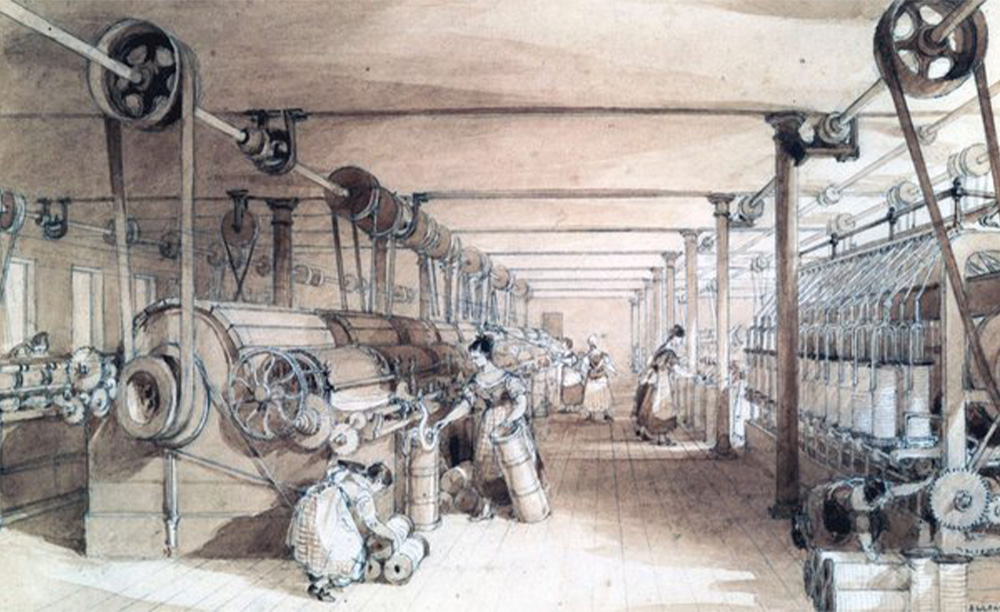

Above: A fairly sanitised interior view of a Victorian cotton mill. The reality would have been a very crowded and noisy workplace, with highly dangerous working conditions.

A Mrs Sterndale visited Cressbrook in 1824 and reported:

The children’s’ hours of work and their necessary relaxation are kindly and judiciously arranged, the former never exceeding that which ought to be exacted from those in their station of life and of their tender age. Their food is of the best quality and amply dispensed and they have eight hours uninterrupted sleep in comfortable beds and airy rooms.

But this doesn’t equate with a report by Sarah Carpenter who was forcibly taken in the dead of night, and without her widowed mother’s knowledge, from a Bristol Workhouse aged just eight in around 1820:

Our common food was oatcake. It was thick and coarse. This oatcake was put into cans. Boiled milk and water was poured into it. This was our breakfast and supper. Our dinner was potato pie with boiled bacon it, a bit here and a bit there, so thick with fat we could scarce eat it, though we were hungry enough to eat anything.

Tea we never saw, nor butter. We had cheese and brown bread once a year. We were only allowed three meals a day though we got up at five in the morning and worked till nine at night.

Punishment at the mill was extremely harsh. The master carder’s name was Thomas Birks; but he never went by any other name than Tom the Devil. He was a very bad man – he was encouraged by the master in ill-treating all the hands, but particularly the children.*

Newton died in 1830 and five years later Francis Phillips sold the mill to Henry McConnel. The supply of water from the Wye was often a problem when the river ran low. Improvements included creating a mill pond fed by Cress Brook, and installing a steam engine. Water turbines were introduced in 1890.

McConnel built Cressbrook Hall, and also created a ‘model village’ for his workers which today forms the village of Cressbrook. This was extended by his daughter, Mary Worthington, in 1902 to include a village club, modelled on a working men’s club.

The mill finally closed in 1965, lying derelict for many years until it was converted into apartments in 2000.

*Click here to read a more complete transcript of Sarah’s testimony.