Above: The panoramic view from Monsal Head with the Monsal Trail running along Headstone Viaduct at bottom left.

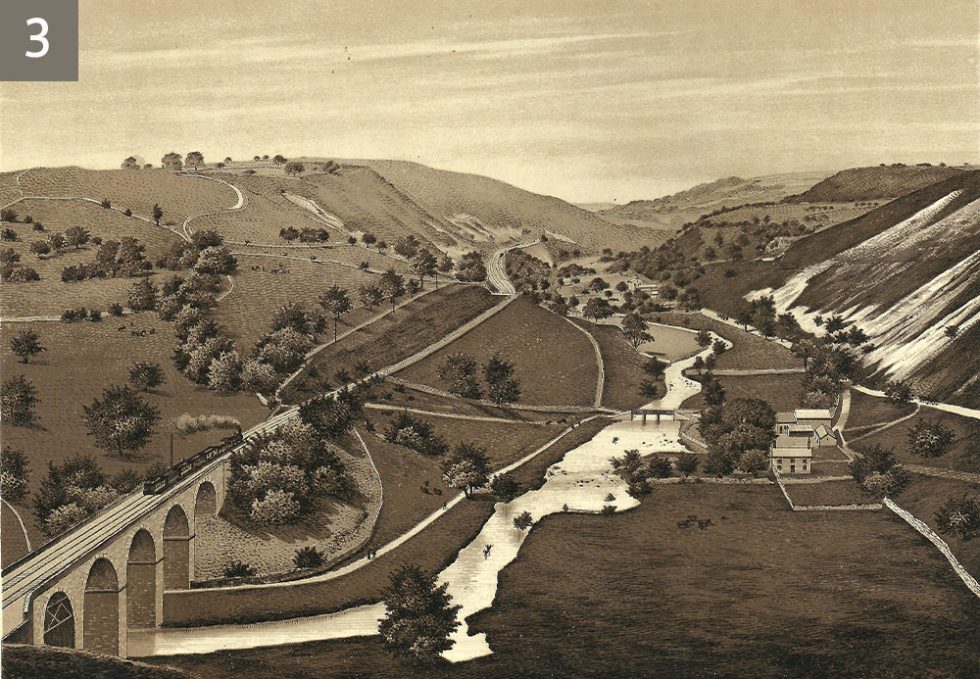

Above: This painting is from Buxton Museum’s collection (click to enlarge).

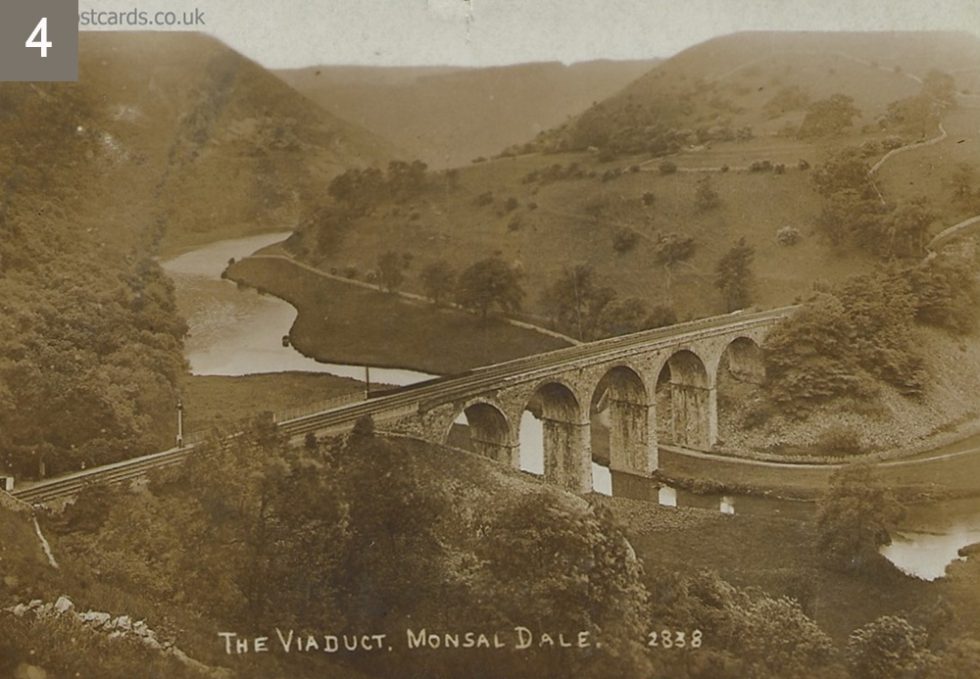

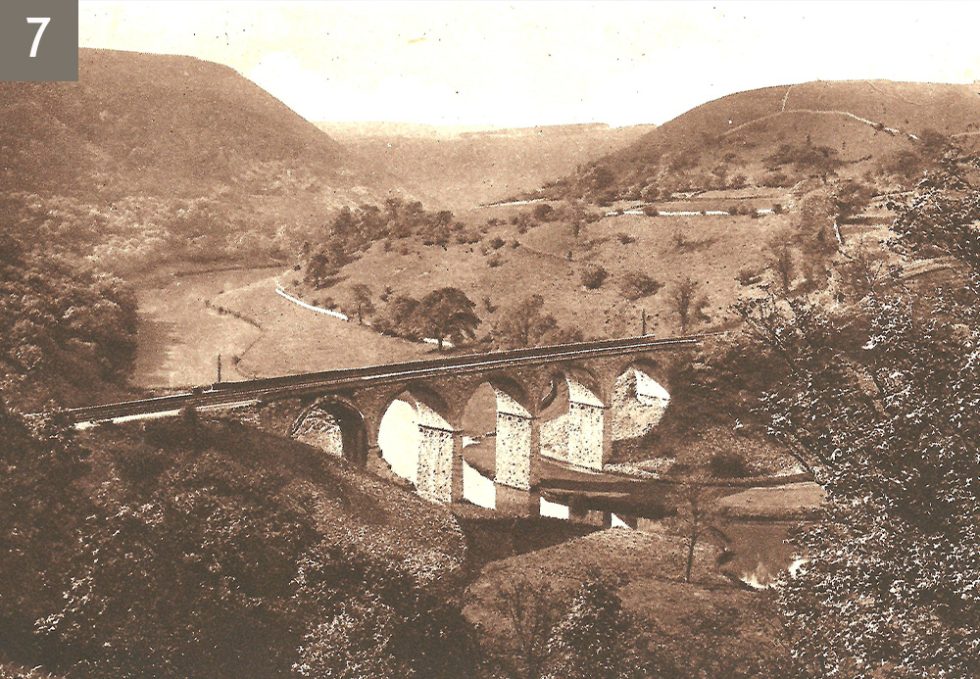

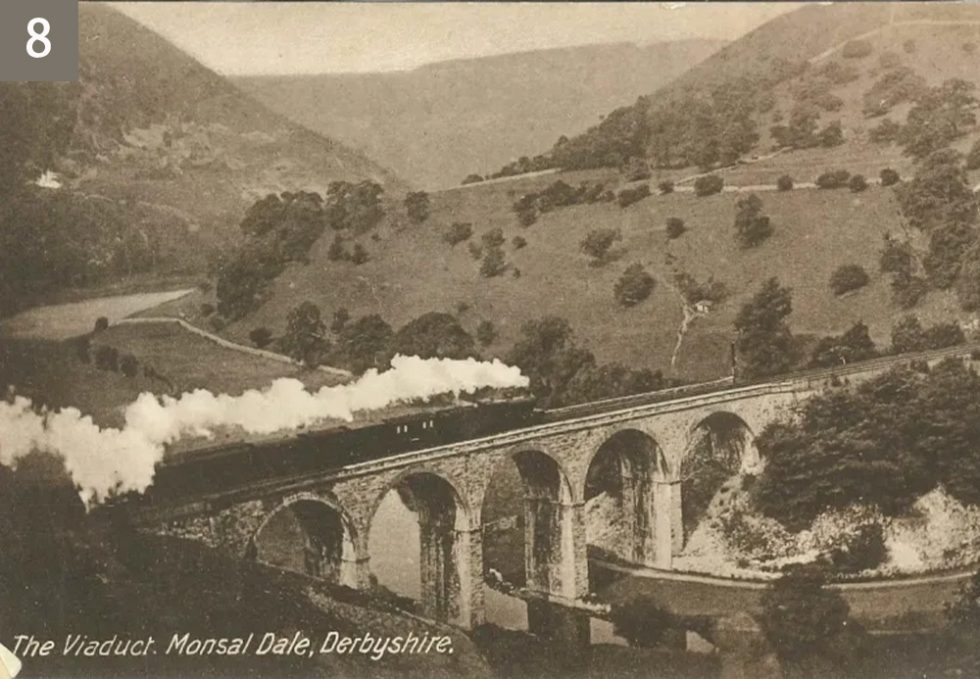

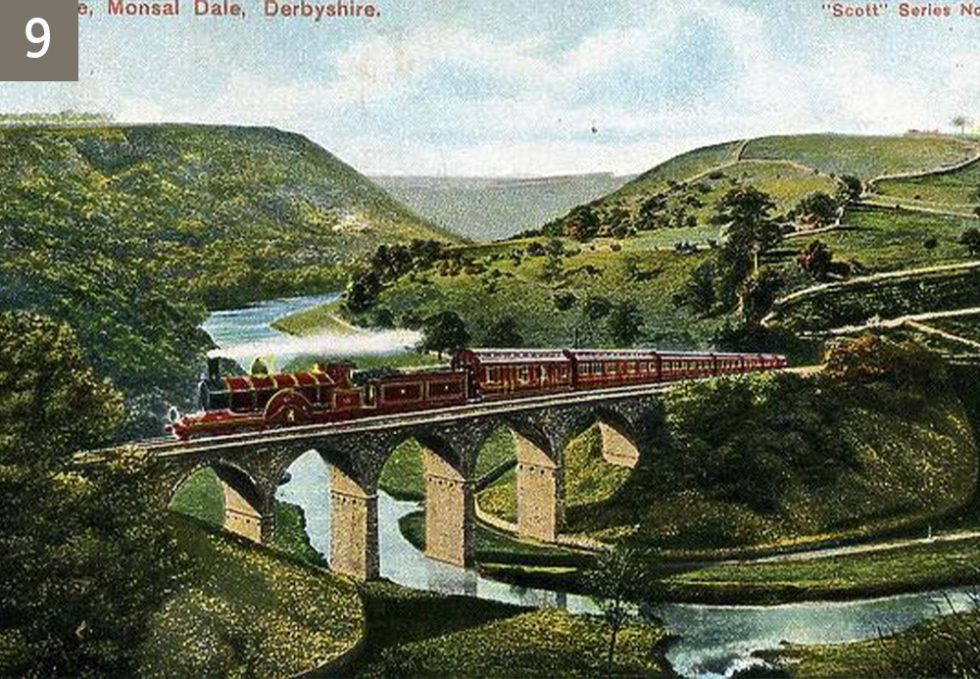

The glorious view from Monsal Head looking down to Headstone Viaduct spanning Monsal Dale and the River Wye far below has long inspired artists and photographers, as well as anyone resting awhile on the nearby benches.

At 300 feet long, with five arches reaching some 70-feet at the centre, it appears a triumph of Victorian engineering. But it wasn’t met with universal approval when work started around 1860. Victorian artist and critic, John Ruskin, famously complained:

There was a rocky valley between Buxton and Bakewell, once upon a time, divine as the Vale of Tempe. You enterprised a Railroad through the valley – you blasted its rocks away, heaped thousands of tons of shale into its lovely stream. The valley is gone, and the Gods with it; and now, every fool in Buxton can be in Bakewell in half an hour, and every fool in Bakewell at Buxton; which you think a lucrative process of exchange – you fools everywhere.

In some ways it’s easy to see why he objected. After all, if it had been built as a road bridge, with a never-ending stream of cars and lorries crossing the valley, I’m sure we’d have complained just as bitterly!

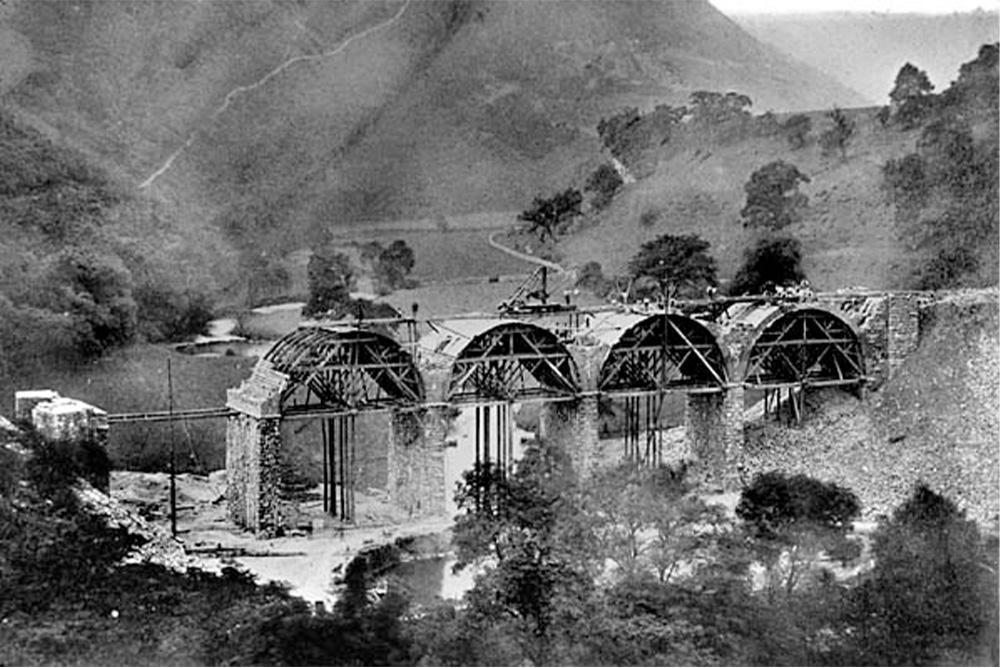

Above: This 1860s view of the viaduct under construction shows why Ruskin wasn’t so keen on the plan (click to enlarge).

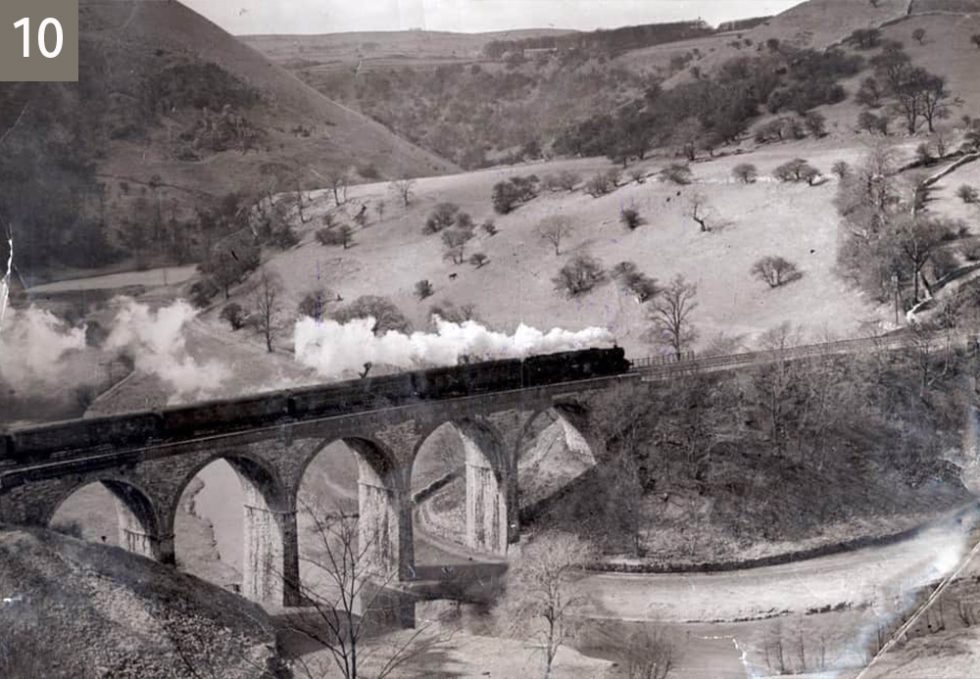

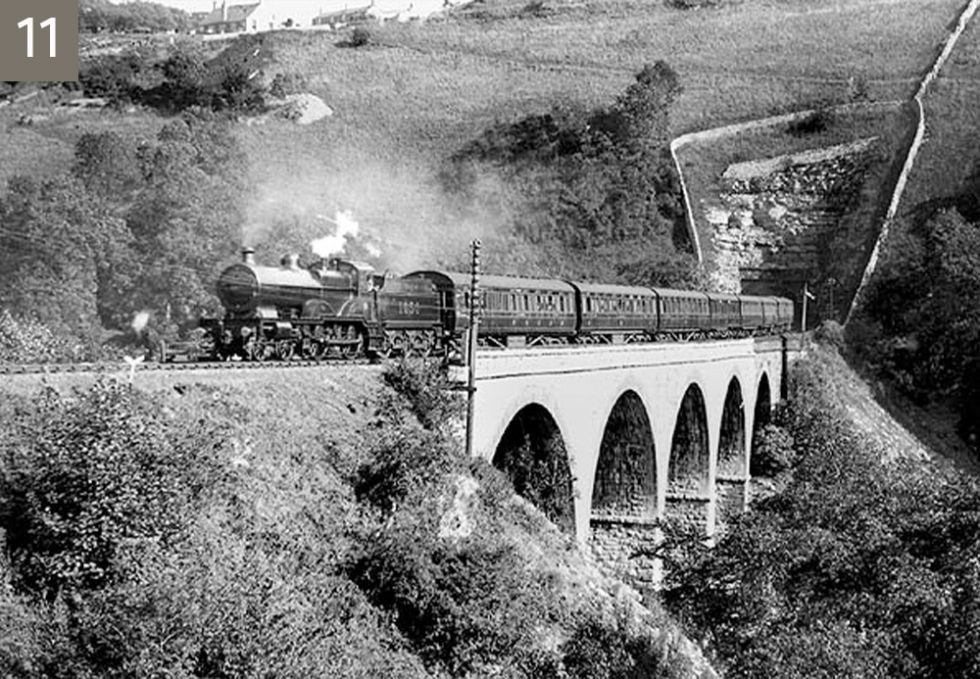

Steam trains first powered their way across the viaduct in 1863, with the opening of a new route between Ambergate and Buxton (view brief history of the line). Some four years later, it was extended to Manchester, providing a connection between the fast-expanding city and London St Pancras.

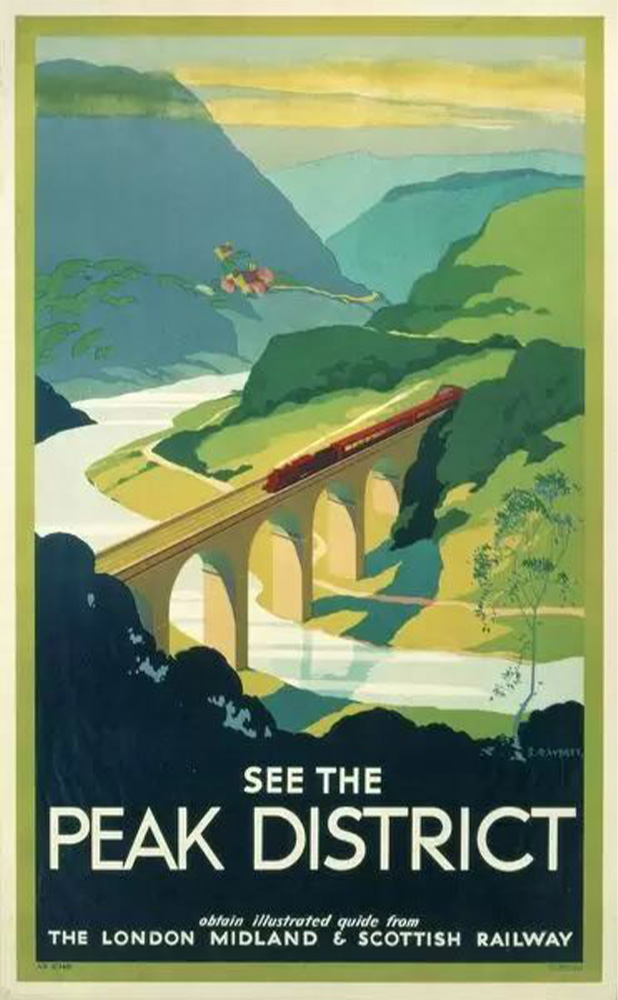

Above: Headstone Viaduct featured in a number of railway posters. This one dates from the time of the London Midland & Scotland Railway; between 1938 and nationalisation in 1948.

Above: Click the ‘Then’ button, or drag the green slider, to compare an 1890s map with today’s satellite view. It reveals just how much stone was used to buttress either ends of the viaduct, greatly narrowing Monsal Dale at this point.

For many decades the line proved highly profitable, but by the 1950s things had started to decline with an increase in car ownership, and companies shipping goods by road rather than rail.

Dr Beeching’s 1963 report sounded the death knell of the line by recommending the closure of all the small stations along the track. And in 1968 the final Intercity train ran across the viaduct. It then lay derelict for the next 13 years until the Peak District National Park took ownership to create the 8.5-mile Monsal Trail for walkers in 1981.

Opening the tunnels

Headstone tunnel is next to the eastern end of the viaduct. At 533 yards, it was the longest of six tunnels on the line. Even though the trail was opened in 1981, it would be another 30 years – in 2011 – before wakers were allowed through them, rather than having to make their way around some fairly steep and narrow tracks.

A few walks on this website start from Monsal Head and pass over the viaduct, including this one to Litton Mill.

Photo gallery

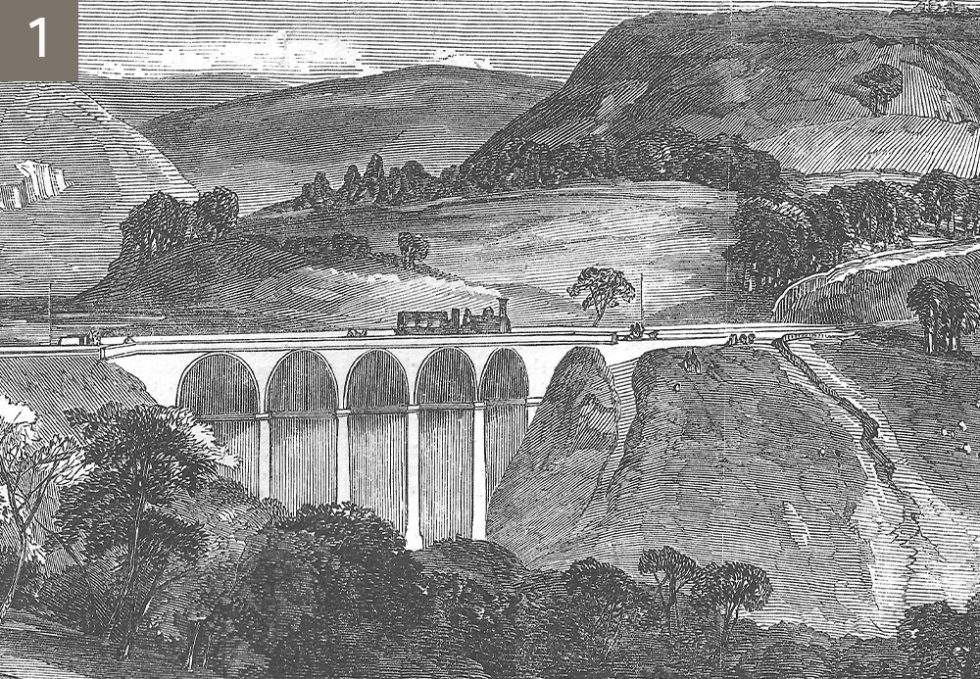

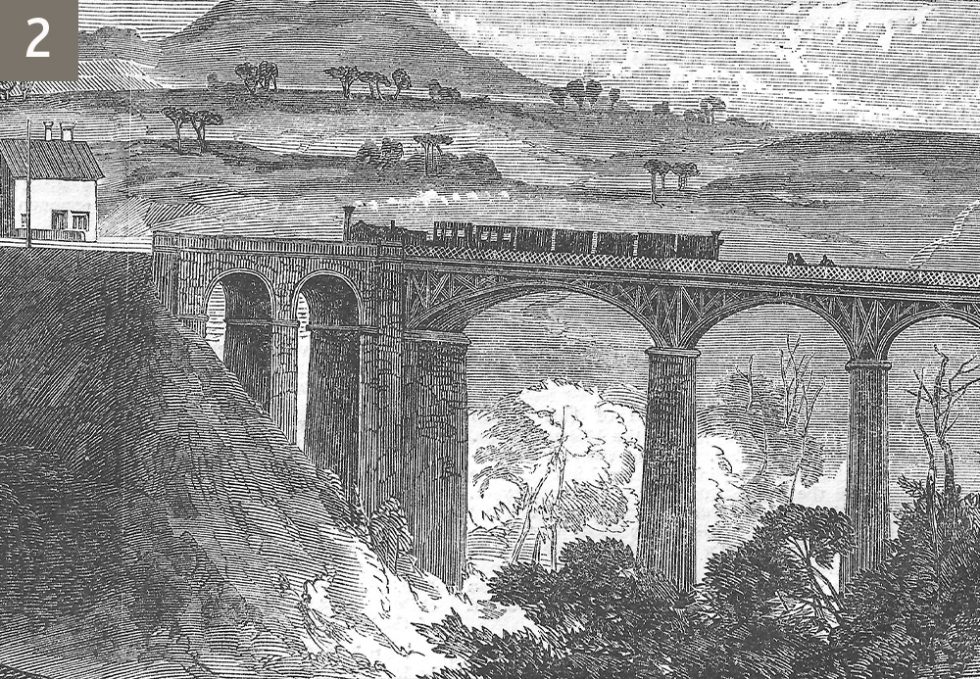

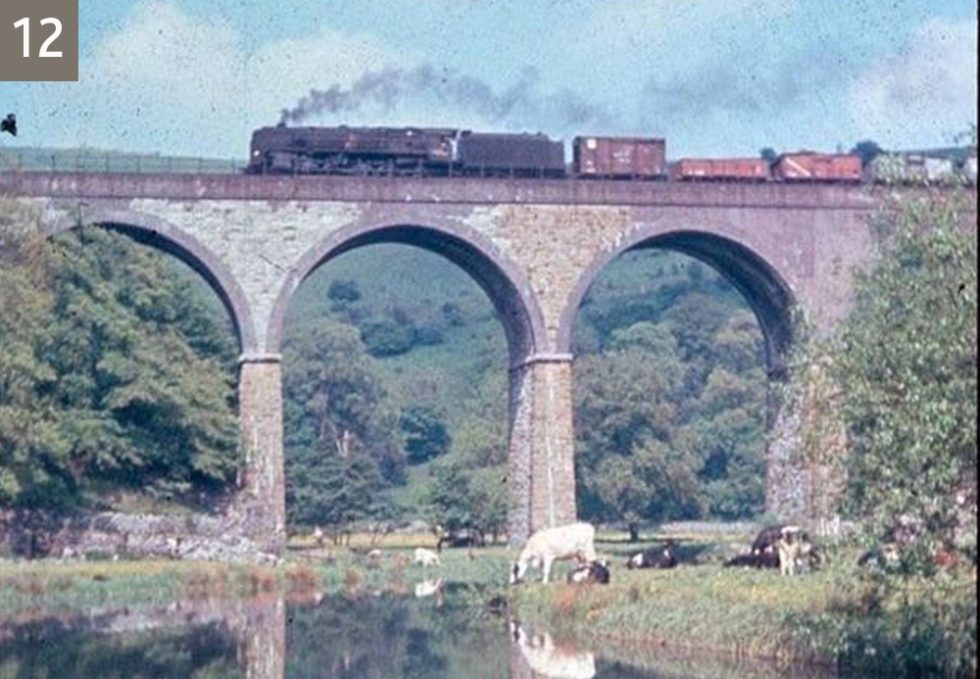

Click on any photo to enlarge and use the arrow keys to scroll through. I’ve tried to put them in date order using the vegetation on the shale buttress supports as a clue. (Photos 1, 2 & 3 courtesy of Alan Roberts.)

I noticed on my visit, and it can be seen in photo 12, that the viaduct´s sides are built with two differently coloured stones as well as blue bricks. Is this original or the result of a defect or rebuild?

Photo, or rather woodcut 2 seems to be the viaduct at Miller´s Dale.